This study aims to analyze the phases in industrial production cycles and the contribution of the recently introduced measures and incentives to the recovery in industrial production, in a sectoral breakdown. The primary objective is to shed light on the process through which the recent slowdown in industrial production gave way to recovery from end-2016 onwards. The study examines the course of economic activity from a cyclical perspective and employs some technical terms peculiar to this perspective. These technical terms and the method of calculating cyclical movements are explained in Özbilgin (2017) in detail. To guide the readers, a visual definition of the terms used in this paper is offered in Chart 1.

The economic activity measured by the Industrial Production Index (IPI) started slowing in cyclical terms by the last quarter of 2015 and assumed a recovery trend as of end-2016 (Chart 2). In April 2017, the potential threshold was slightly surpassed and the expansion period began.

Let us start examining the drivers of the recovery by analyzing the cyclicality in core goods groups. As shown in Chart 3, the recovery in the IPI is driven by the sectors producing durable goods, energy and capital goods. The slowdown in the recent past was most visible in the durable goods sectors but it was also these sectors that registered the most rapid recovery. The Chart also shows that the recovery in sectors producing intermediate goods continues but still remains below the potential. On the other hand, the negative outlook in the non-durable goods group persists. Although there are signals of a recovery in this group, these signals are weak and the slowdown goes on as of the second quarter of 2017.

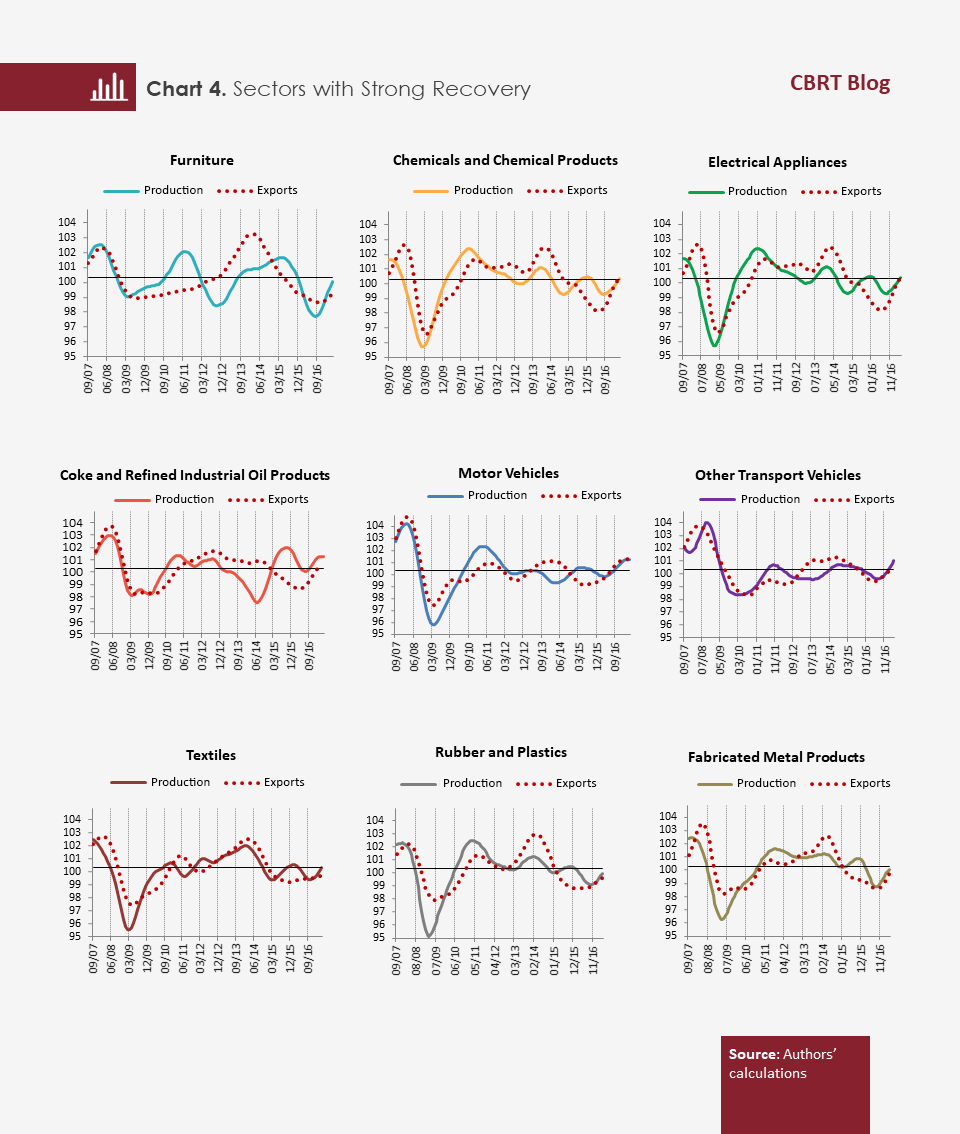

We will now try to figure out the sectoral components of recovery. Chart 4 displays the sectors with a strong recovery trend. These sectors account for almost half of the total value added of the manufacturing industry. Among these sectors, the furniture and the electrical appliance sectors were the sectors that were most deeply affected by the latest slowdown. It is clear from the charts that the tax deductions in these sectors (coupled with the effect of the exchange rate advantage-driven acceleration in exports) were instrumental in the rapid recovery we observed and that these policies were well-timed.

In the remainder of this study, we analyze the sectors triggering the recovery in the IPI by making some inferences about the role of sectoral export developments, incentives and tax deductions. Table 1 shows the sectoral distribution of incentive expenses between October 2015 and April 2017. From the beginning of the slowdown in the IPI to the date when the potential was exceeded again, sectoral incentive expenses amounted to approximately TL 45.9 billion. These expenses were mostly composed of investment, export, employment, entrepreneurship, exhibition and R&D incentives as well as other sectoral/regional incentives.

The effective dates of the incentives given in Table 1, and the quality and nature of incentive expenses differ significantly across sectors. For example, while boosting demand is the direct target in some sectors and thus tax deductions are introduced for consumers, R&D and innovation expenses are subsidized in some other sectors to achieve long-term productivity. While incentives offered to a specific sector directly affect that sector, they may also affect other sectors indirectly. The effective dates of incentives differ due to differences in the decision-making and bureaucratic procedures of responsible institutions as well as due to the legislative/executive calendar. Nevertheless, the relationship between the sectoral incentive volume and the sectoral recovery rates can give an idea about the effectiveness of incentives. To this end, using product-based production value data, a sector definition has been formulated at first that will allow a sectoral matching between incentives and components of industrial production index. Next, product-based production values have been aggregated based on these sectors and sectoral production values have been obtained. Then, the shares of incentive expenses in sectoral production values have been calculated.[1] These shares are shown in the x-axis of Chart 5. The y-axis displays a measure that represents the extent of the cyclical recovery (the upward progress that the related series has made after hitting the trough). In the Chart on the left, two outlier sectors have been included as depicted in red on the upper left and the lower right, whereas the Chart on the right lacks these sectors. These are the Electrical Machinery and Machinery Manufacturing sectors.

The framework presented in Chart 5 provides three main insights.

(1) The share of incentive expenses in total production is low in sectors such as the Electrical Machinery sector where the incentives are designed so as to revive, albeit partially, the consumption expenditures in the short term via direct tax deductions. However, the recovery effect is strongly evident in these sectors.

(2) Incentive expenses are high in sectors such the Machinery Manufacturing sector where the incentives are mostly offered in areas such as R&D and innovation that will increase productivity in the long term. However, the recovery effect in the short run is relatively low in these sectors.

(3) Excluding these two sector groups, there is a marked positive relationship between the volume of incentive expenses and the recovery in production.

To conclude, we can say that sectoral measures and incentives play a significant role in the recovery in industrial production. Although the causality cannot be revealed clearly due to data limitations, our calculations suggest that the recovery is more visible in sectors where the volume of incentives is high. Yet, based on the overall observation that the IPI has had difficulty in climbing above the potential level since 2009, it would be better to focus on lasting and sustainable increases in production rather than short-term partial recoveries. In other words, supporting the measures and incentives with structural reforms oriented towards lasting productivity increases is of critical importance to achieving long-term gains in production capacity.

[1] Sectors with a relatively low share in total production, which do not allow for a definition matching, are excluded from the analysis.

Bibliography

Özbilgin, M. (2017). “Forecasting the Growth Cycles of the Turkish Economy” CBRT Working Paper, 17/15.