Whenever exchange rate displays a sharp movement, the pass-through effect to inflation becomes a frequently debated issue in reports and commentaries regarding monetary policy. Indeed, this is understandable because exchange rate is widely recognized as one of the primary determinants of inflation.[1] In this respect, the main question analysts seek to answer is the impact of exchange rate movements on consumer inflation. Is there a coefficient that would be applicable at all instances of exchange rate pass-through to inflation? In other words, what will be the impact of a one percent depreciation in domestic currency on inflation?

Studies conducted by the CBRT staff and academics offer some estimates of the exchange rate “pass-through coefficients”. These coefficients are useful for providing an overall idea but they may also be misleading when individually used regardless of the factors that can affect pass-through. For instance, when making inflation forecasts, it may not be correct approach to simply multiply the exchange rate depreciation rate with a fixed coefficient and add it to the current inflation rate. Why is this so? Because the pass-through impact may vary depending on the underlying economic environment. In this post, we aim to provide some insight to clarify certain issues regarding this subject. Based on the findings of the CBRT’s studies, first we explain why the pass-through effect should not be calculated in such a mechanistic way. Next, using this background, we offer our view on the likely pass-through dynamics of recent exchange rate movements to domestic prices.

Why and How Do Exchange Rate Movements Pass-Through to Prices?

The most direct channel works through the imported consumer goods, as the consumer price basket contains directly imported goods such as automobiles and cell phones. The exchange rate may also affect inflation through imported inputs (energy and other intermediate goods) used in production.[2] These effects are called as the “cost channel”.

Hence, the import share of consumption and the share of imported inputs in total production costs affect the exchange rate pass-through. Larger share of imported goods in the consumer basket or higher share of imported intermediate goods in the production of consumer goods are typically associated with higher pass-through. Previous studies suggest that, due to high import component in production, the impact of exchange rates on prices is widely dispersed across sectors in Turkey.[3]

In addition to import and cost channels, exchange rates may also have an impact on the pricing behavior through the indexation channel, which has close interaction with inflation expectations. Studies on Turkey indicate that in the high-inflation environment prior to the floating exchange rate regime, the sensitivity of inflation to the exchange rate could be high even in sectors such as the services where the imported input rate is relatively low.[4] This can be explained by the indexation behavior which has emerged as a motive to protect against high inflation. Inflation fighting credentials of the economic policies are likely to mitigate the indexation channel.

Related studies also indicate that the indexation behavior and exchange rate pass-through weakened in the aftermath of transition to the floating rate regime in Turkey.[5] What is more, the speed, as much as the extent, of the pass-through from exchange rates to inflation has shown a marked decline. In the pre-floating exchange rate regime, exchange rate pass-through was fast, yet in the period afterwards, the pass-through is experienced more slowly and gradually. This situation points to the role of expectations regarding the persistence of exchange rate shocks in explaining the pass-through effect. Furthermore it is frequently emphasized in literature that a low inflation environment weakens the link between the exchange rate and inflation.

Is There a Magical Coefficient?

Up-to-date studies regarding Turkey suggest that the cumulative pass-through from exchange rates to prices after one year is around 15 percent.[6] Well then, do we have to read it as a magical number? Our answer to this question is explicitly and definitely: NO.

Above all, it should be underlined that most of the previous studies estimate the “average” historical effect. This average coefficient can show significant variability according to the economic environment and the business cycle.[7] As a matter of fact, our recent study reveals that the magnitude and timing of this average effect can differ depending on a number of factors. Among these, the cyclical situation of the economy (expansions and downturns), exchange rate expectations (the perception that movements are transient/persistent), and the magnitude of the exchange rate shock can be noted as primary factors affecting the pass-through.

Now, using this background, let us try to evaluate the current situation regarding the pass-through effect. To this end, we will address two major factors that may have an impact on the pass-through in the current situation: (i) Business cycle (ii) Exchange rate expectations.

Pass-Through and the Business Cycle

Our findings suggest that the exchange rate pass-through weakens during economic downturns (when the output gap is negative), whereas it strengthens during booms (when the output gap is positive).[8] In interim periods where the economic activity is close to its potential, the pass-through hovers generally close to historical averages.

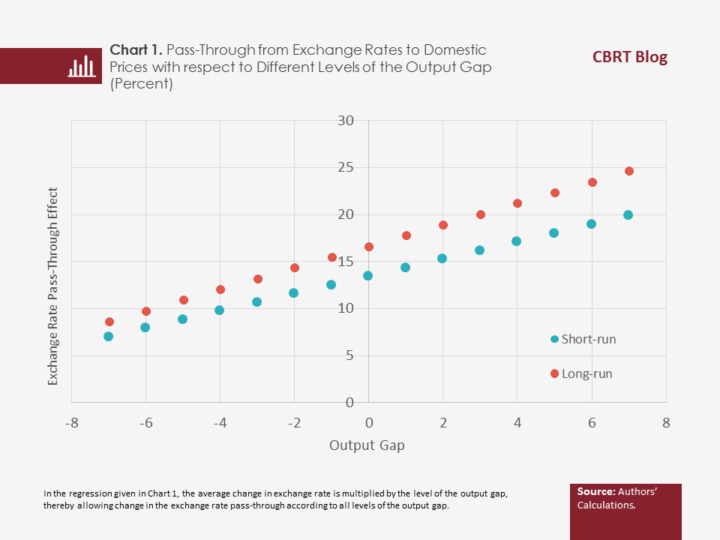

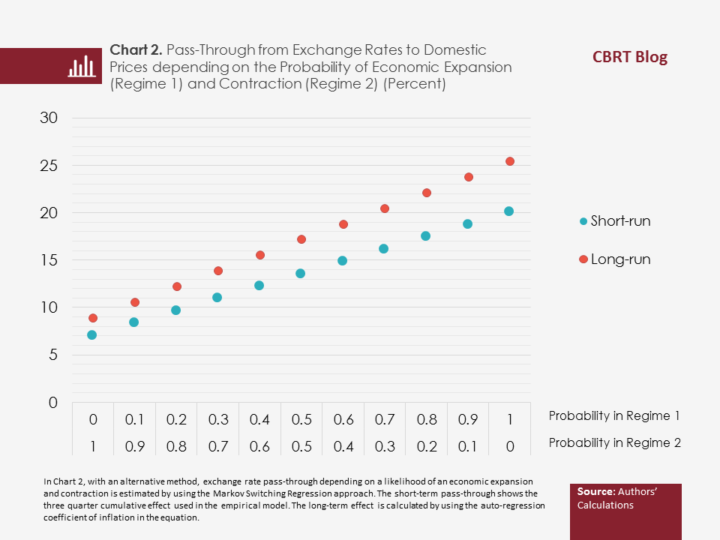

As illustrated in Chart 1, when the economy is at the potential level (output gap is close to zero), the exchange rate pass-through materializes around 15 percent; however, the same chart also shows that this coefficient may vary depending on the cyclical fluctuations in the economic activity. While the exchange rate pass-through reaches some 25 percent levels during over-heating periods, it may fall below 10 percent during cooling periods. As an alternative method, using Markov switching regressions, we estimate the probabilities attributed to the periods of expansion and contraction, which has yielded similar findings (Chart 2).

The Turkish economy displayed a milder growth in 2016 compared to previous years, on the back of the economic slowdown in the second half of the year. Economic recovery is projected to be gradual and moderate in 2017. Therefore, it can be asserted that, ceteris paribus, the pass-through coefficient is likely to be below the historical averages.

Pass-Through and Expectations

But the above analysis should be interpreted with caution. It can be misleading to estimate the degree of pass-through from exchange rates to prices by only conditioning on the output gap, because, as we have already pointed out, business cycle is not the only factor influencing the pass-through. The forward looking nature of the exchange rate makes the expectations channel important in price decisions. Therefore, perceptions of the persistence of an exchange rate movement (whether it will be temporary/ permanent), or expected level of exchange rates may play an important role in the pass-through process.

To this end, we look at the survey results to have an idea regarding exchange rate expectations. We use the “Expected USD/TRY rate depreciation over the next 12 months” indicator that is calculated based on data from the Survey of Expectations conducted by the CBRT (Chart 3). We analyze whether the exchange rate-inflation relationship changes with the extent of expected depreciation.

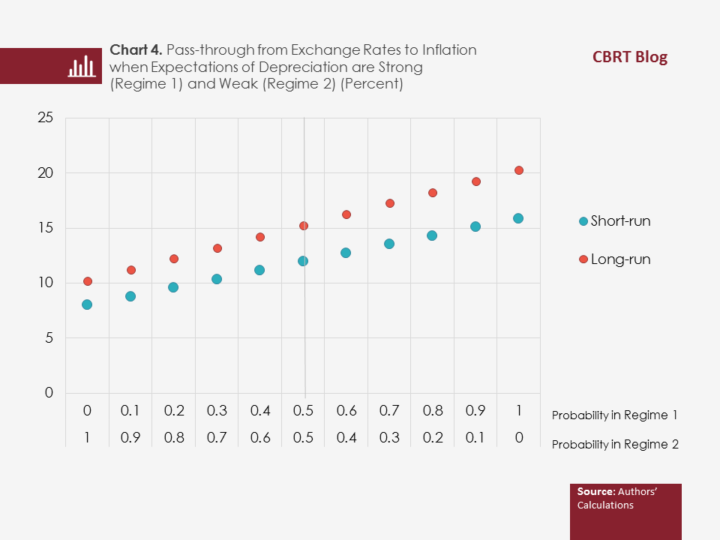

Our findings confirm that expectations are also an important determinant of the exchange rate pass-through to inflation. We find that when markets expect a strong depreciation, the relation between exchange rates and inflation is higher than historic averages. Whereas, in periods of appreciation or mild expected depreciation, this impact is much lower (Chart 4). Turning to the current situation, these observations suggest that exchange rate expectations should be monitored closely in terms of their implications on the pricing behavior.

Conclusion

To sum up, our findings indicate that there is no fixed magical coefficient for the degree of pass-through from exchange rates to prices. For instance, currently, the weak course of the economic activity is limiting the exchange rate pass-through. On the other hand, expectations might be working in the opposite direction. The persistent depreciation trend since mid-2013 and its possible impact on the expectation formation pose upward risk for the overall pricing behavior (Chart 3). Therefore, the degree of pass-through in the upcoming period will likely be determined by a tug of war between these two factors.

Lastly, it is worth to say a few words on the structural roots of the exchange rate-inflation relationship. Even if our analysis implies that pass-through coefficient differs with cyclical factors, it doesn’t change the fact that the eventual historical impact is still sizeable. Therefore, we need to keep in mind that it is the structural measures that would weaken the relation between exchange rates and prices in the medium and long run. To this end, increasing domestic value added component of production, reducing dollarization, managing exchange rate risk to bolster financial stability, and a concerted effort to establish price stability are crucial structural factors to be addressed in the forthcoming period.

[1] Annual consumer inflation in Turkey was 8.2 percent on average during the inflation targeting period between 2006 and 2015, where the average contribution of exchange rate movements to inflation was calculated as 1.1 points per year (CBRT, 2016a). This contribution rose to 1.8 points in the more recent period of 2011-2015.

[2] For example, in addition to their direct impacts, oil products have also indirect (cost-side) impacts on consumer inflation as they constitute an important input in production and transportation. See, Balkan, Kal and Tümen (2015).

[3] Atuk, Aysoy, Özmen and Sarıkaya (2014) and Özmen and Sarıkaya (2014) suggest that a significant portion of the CPI basket in Turkey is not sensitive to business or credit cycles and that the inflation in related groups is mainly determined by Turkish lira-denominated import prices. Özmen and Topaloğlu (2017) find that the exchange rate pass-through to inflation varies in CPI subgroups and it is at a significant level in the food group as well.

[4] Kara, Küçük, Özlale, Tuğer, Yavuz and Yücel (2005).

[5] For studies comparing the exchange rate pass-through before and after the inflation targeting period, see Kara and Öğünç (2008), Damar (2010) and Yüncüler (2011).

[6] See Kara and Öğünç (2012). It is possible to obtain different estimates depending on the method or sample period. See CBRT (2016b), Özmen and Topaloğlu (2017).

[7] For other studies regarding asymmetric exchange rate pass-through effect, see Arbatlı (2003), Kara, Küçük, Özlale, Tuğer, Yavuz and Yücel (2005), Kal, Arslaner and Arslaner (2015).

[8] In the time of overheating in the economy, as companies’ pricing power is high due to strong demand conditions, there is a higher tendency to reflect the effect of shock on prices. However, in the time of cooling, this tendency fades away with the lowering profit margins due to weak pricing power.

Bibliography:

Arbatlı, E. C. (2003). “Exchange Rate Pass-Through in Turkey: Looking for Asymmetries”, Central Bank Review, 2, 85-124.

Atuk, O., Aysoy, C., Özmen, M. U. and Ç. Sarıkaya (2014). “Türkiye’de Enflasyonun İş Çevrimlerine Duyarlılığı: Çıktı Açığına Duyarlı TÜFE Alt Gruplarının Saptanması” (Sensitivity of Inflation to Business Cycles in Turkey: Determining CPI Sub-items Sensitive to Output Gap- available only in Turkish) , CBRT Working Paper, 14/37.

Balkan, B., Kal, S. H., S. Tümen (2015). “Akaryakıt Fiyatlarının Nakliye Maliyetleri Kanalı ile Taze Meyve-Sebze Fiyatları Üzerindeki Etkisinin İncelenmesi” (Investigating the Effect of Fuel Prices on Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Prices Through the Transportation Cost Channel- available only in Turkish), Research Notes in Economics, 2015/08.

Damar, A. D. (2010). “Türkiye’de Döviz Kurundan Fiyatlara Geçiş Etkisinin İncelenmesi”(Analysis of Exchange Rate Pass-through to Prices in Turkey- available only in Turkish), CBRT Dissertation, June 2010.

Kal, S. H., Arslaner, F. and N. Arslaner (2015). “Sources of Asymmetry and Non-linearity in Pass-Through of Exchange Rate and Import Price to Consumer Price Inflation for the Turkish Economy during Inflation Targeting Regime”, Research Notes in Economics, 15/30.

Kara, H and F. Öğünç (2008). "Inflation Targeting and Exchange Rate Pass-Through: The Turkish Experience," Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 44(6), 52-66.

Kara, H. and F. Öğünç, (2012). “Döviz Kuru ve İthalat Fiyatlarının Yurt İçi Fiyatlara Etkisi” (Impact of Exchange Rates and Import Prices on Domestic Prices- available only in Turkish), İktisat İşletme ve Finans, Bilgesel Yayıncılık, 27(317), 09-28.

Kara, H., Küçük, H., Özlale, Ü., Tuğer, B., Yavuz, D. and E. M. Yücel (2005). “Exchange Rate Pass-Through in Turkey: Has it Changed and to what Extent?”, CBRT Working Paper, 05/04.

Özmen, M. U. and M. Topaloğlu (2017). “Disaggregated Evidence for Exchange Rate and Import Price Pass-through in the Light of Identification Issues, Aggregation Bias and Heterogeneity”, CBRT Working Paper, forthcoming.

Özmen, M. U. and Ç. Sarıkaya (2014). “Enflasyonun Çıktı Açığı ve Kredilere Duyarlılığı” (Sensitivity of Inflation to Output Gap and Loans- available only in Turkish), Research Notes in Economics, 2014/17.

CBRT (2016a). “Son On Yılda Enflasyon Dinamikleri: Tarihsel Bir Muhasebe” Inflation Dynamics over the Past Decade: A Historical Accounting), Inflation Report 2016-IV, Box 3.1, 32-36.

CBRT (2016b). “Türkiye’de Enflasyon Dinamiklerine Bayesçi Bir Yaklaşım”(A Bayesian Approach to Analyzing Inflation Dynamics in Turkey), Inflation Report 2016-I, Box 3.2, 34-37.

Yüncüler, Ç. (2011). “Pass-Through of External Factors into Price Indicators in Turkey”, Central Bank Review, 11, 71-84.