Wages play a major role in inflation through cost-push and demand-pull factors. Moreover, their sensitivity to business cycles is a key issue for the way inflation reacts to economic shocks and for the effectiveness of monetary policy. Therefore, for a better understanding of economic dynamics, it is crucial to draw an outline of the distribution of wages in Turkey and explain how wages are determined. So, what data are needed to track wage changes?

Wage Indicators

A key statistic for wage costs is the “hourly labor cost index” under the labor input indices (LII) announced quarterly by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT) (Table 1). The “real unit labor cost”, which plays a key role in inflation dynamics, is also monitored. This indicator measures the real cost of labor per unit of value added produced. On the income front, the Social Security Institution’s (SSI) “average daily earnings” and the “gross wages and salaries index” under the TURKSTAT’s LLI are among the top wage indicators to follow. TURKSTAT’s gross wages and salaries series consist of regular wages and bonuses as well as all non-monthly irregular earnings, whereas the SSI’s wage index covers only a part of these irregular earnings as it is built on whether earnings are premium-based or not.

Wage Distribution in Turkey

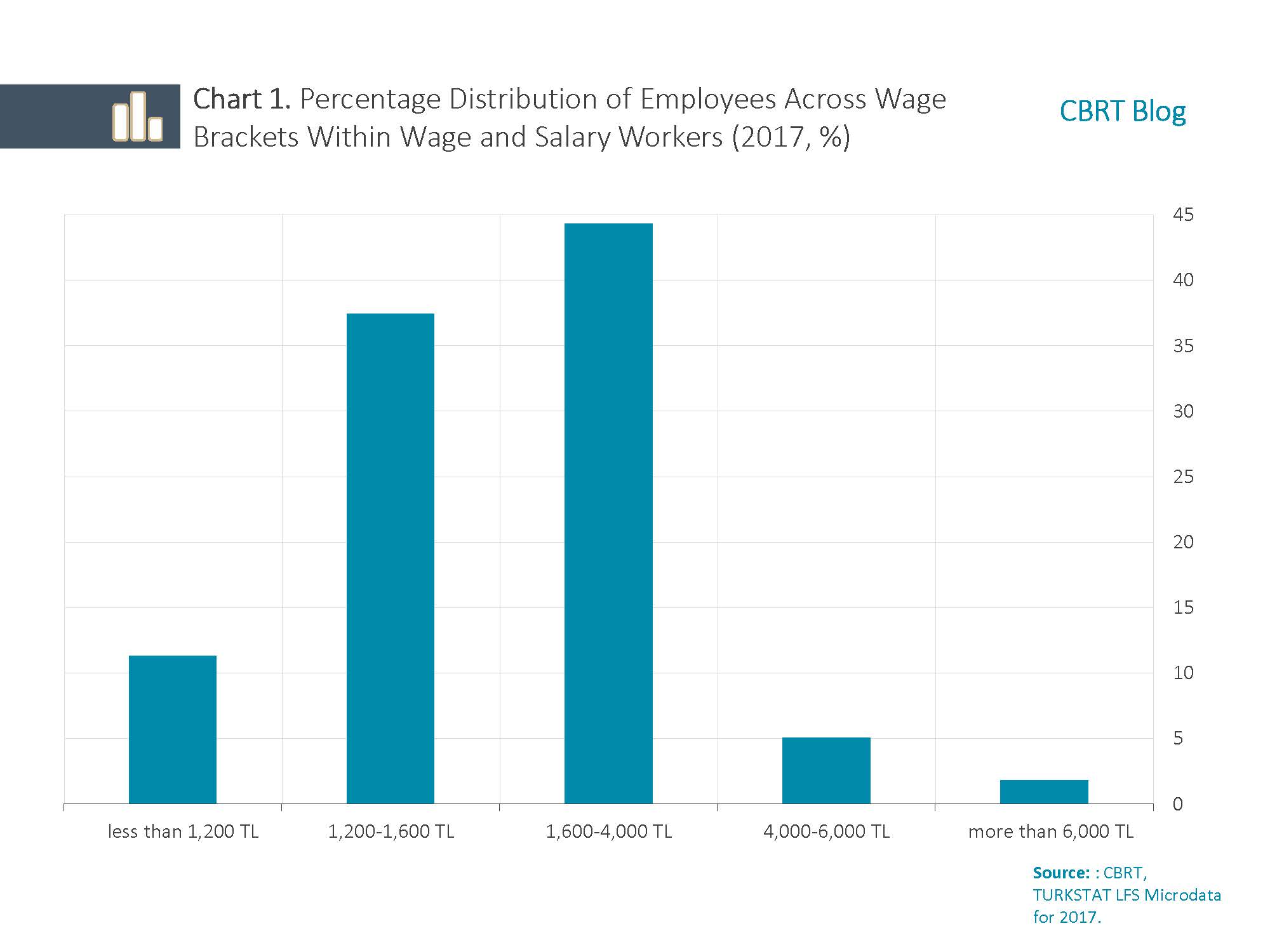

Another question in hand is how wages are distributed in Turkey. To answer this question, one may analyze wage and salary employees using micro data from the Labor Force Survey (LFS) of 2017. The LFS is a household survey that provides information on total net cash income (in addition to earnings paid to employees, benefits in cash and in kind, bonuses and premiums, etc.) received in the previous month. Accordingly, as of 2017, wage and salary workers account for 67.3% (18.9 million people) of total employment. Across wage brackets, 11.3% of wage and salary workers received an income less than 1,200 TL, while 37.5% earned in the neighborhood of the minimum wage (1,200-1,600 TL) and 44.3% declared an income between 1,600 TL and 4,000 TL (Chart 1).

In sum, about two-thirds of total employment is composed of wage and salary earners, while half of them earn around and under the minimum wage. In other words, the share of employees who receive an income around or less than the minimum wage is about one-third of total employment. Therefore, the minimum wage rate is an imperative factor for both economy-wide wage increases and wage distribution. Yet, what are the other factors that influence increases in wages other than the minimum wage?

Factors to Consider When Determining Wage Increases

In order to answer this question, we first examine labor agreements to capture the indexation behavior.

Collective labor agreements (CLA) point to a high degree of backward indexation in wage increases. Excluding the abnormal yearly minimum wage changes of the 2016-2017 period, the increase was about 3.0 percentage points above the expected inflation. Looking at CLAs and the labor agreements announced on the Public Disclosure Platform (PDP), one can see that wages increased at a faster pace than the expected inflation rate in the first year of the CLA and the rate of increase in the following periods was as much as the actual inflation rate of the previous year (or the previous six months) (Table 2).

An alternative method to better understand the factors that determine wage increases is the empirical modeling of wage series. To do this, we look at a number of studies carried out by Bank staff. Studies focusing on wage dynamics confirm that past inflation and the minimum wage increase have a significant impact on non-agricultural wage rates. In addition, business cycles are found to have a particularly noticeable impact on wages in upper income brackets. Wages around and under the minimum wage are immune to business cycles, while wages above the minimum wage are more sensitive to business cycles. The statistically significant and relatively large coefficient of past inflation found in these studies indicates the importance of backward indexation in determining wage increases, as seen in CLAs.[1]

In conclusion, a considerable proportion of wage and salary employees in Turkey earn wages at and around the minimum wage, and minimum wage rates and the CPI serve as an anchor for wage increases in the private sector. This mechanism limits the sensitivity of wages to business cycles across the economy, leading to a significant rigidity in wage inflation and feeding into inflation rigidity in terms of the interaction between wages and inflation.

[1] For more detail, see Aldan and Gürcihan Yüncüler (2016) and CBRT (2018a) studies.

References

Aldan, A. and Gürcihan Yüncüler, H. B. (2016). “Real Wages and the Business Cycle in Turkey”. CBRT Working Paper, No. 16/25.

Gürcihan Yüncüler, H. B. and Yüncüler, Ç. (2016). “Minimum Wage Effects on Labor Market Outcomes in Turkey”. CBRT Working Paper, No. 16/14.

CBRT (2018). “Understanding Turkey’s Wage Dynamics”, Inflation Report, Issue 2018-IV, Box 4.1, pp. 54-57.