Exports are important especially for emerging economies like Turkey. As exports is one of the key drivers of economic growth, fluctuations in exports, whether sector-based or at the macro level, adversely affect exporters’ investment plans by fueling uncertainties, and thus restrain their growth performance. Fluctuations in export revenues are most clearly observed during economic turmoil. Understanding the conjunctural and behavioral components affecting firms’ export decisions during crisis periods can significantly contribute to designing effective policies supporting economic stability.

This post summarizes our findings regarding the impact of economic fluctuations on firms’ export decisions[1]. The analysis, which was carried out with 108,085 observations from 12,431 firms that were active in the manufacturing sector between 1990-2014, indicates that firms are determined to continue export activities. Only 7 percent of exporters stopped exporting from one year to the next, while 20 percent of non-exporters decided to become exporters within a year[2]. Trends in entering into and surviving in export markets do not exhibit a significant change over time; however, crisis periods are an exception[3]. Actually, trends in export decisions vary in crisis periods with different peculiarities. Moreover, we have also observed that the composition of firms that change their export decisions is also diversified in different types of crisis periods.

The core objective of this study is to reveal that crises with different characteristics and dynamics can affect firms’ export decisions via different mechanisms. Therefore, we focus on the crises of 1994, 2001 and 2008 that Turkey went through and try to explore how firms’ export behavior changed during these different economic crises.

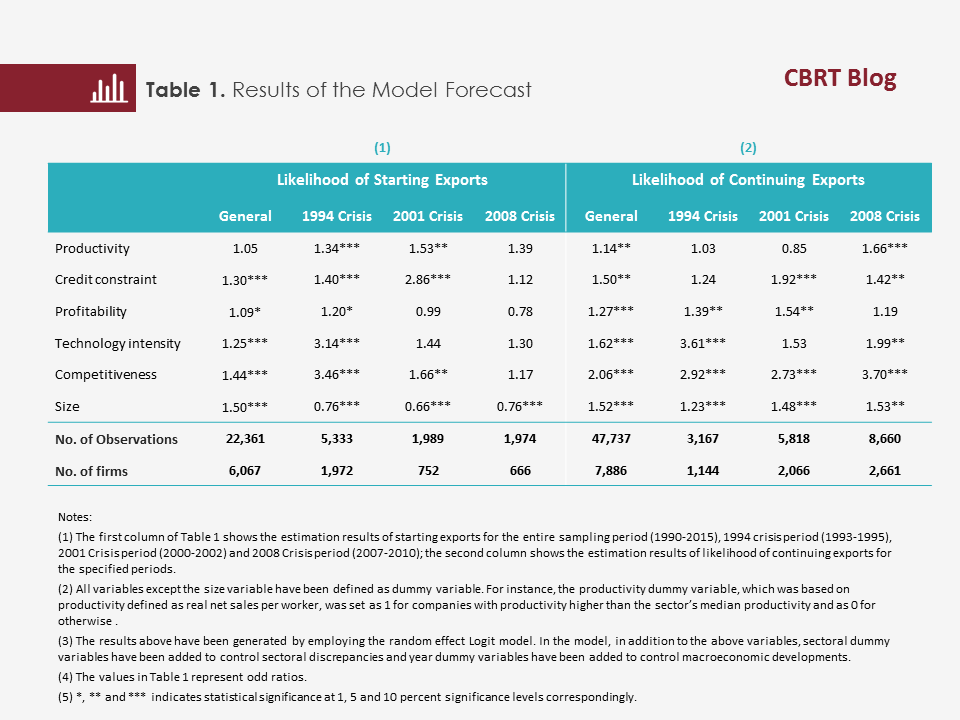

Table 1 shows the results of an econometric analysis pertaining to firms’ likelihood of becoming an exporter and continuing exporting at times of different crises.

Firm Characteristics Affecting Likelihood of Starting Exports and Surviving in Export Markets

Size, credit constraint, profitability and R&D investments are the factors affecting a firm’s likelihood of becoming an exporter. Same factors are also important for the survival of exporters in the export markets. While productivity does not influence firm’s likelihood of becoming an exporter, it increases an exporter’s likelihood of survival in export markets.

It is observed that after controlling the size and sectoral differences, firms with higher intangible competitiveness are 1.44 times more likely to become exporters. Likewise, the likelihood of becoming an exporter for firms that make R&D investments is 1.25 times higher than those with no R&D investments. Similarly, the likelihood of starting exports for firms with no credit constraints is 1.3 times higher than a firm with credit constraints.

While the likelihood of continuing export activities for firms with higher intangible competitiveness is approximately 2 times higher than those with lower intangible competitiveness; the likelihood of staying in the export markets for firms making R&D investments is 1.6 times higher than those with no R&D investments. Exporters with no credit constraints and with high profitability are 1.5 and 1.1 times, respectively, more likely to survive in export markets compared to companies with credit constraints and low profitability.

In the related literature, advertisements, marketing and post-purchase services are regarded as intangible competitiveness and are used as an indicator of quality production together with R&D investments. In this respect, our estimation results suggest that “quality production” is important for starting exports and surviving in the export market.

Tendency to Start Exports

The firm characteristics that affect a firm’s likelihood of entering export markets during crisis periods differ from the general trend. During 1994 crisis, when domestic demand significantly contracted and the Turkish lira depreciated, the impact of quality production on the likelihood of becoming an exporter was more significant. During the same period, the likelihood of becoming exporters for firms with R&D investments was 3 times higher than those with no R&D investments and the same likelihood for the firms with higher intangible competitiveness was more than 3 times higher when compared to firms with lower intangible competitiveness.

During the 2001 financial crisis, which was rather a crisis of domestic nature and characterized mainly by significant credit shortage, the most important factor determining the likelihood of becoming an exporter was credit constraints. Contrary to the general trend, R&D expenditures and profitability lost their importance relatively, while the likelihood of becoming an exporter for the firms without credit constraints was 3 times higher than those with credit constraints.

During the 2008 financial crisis, which led to a sharp foreign demand contraction especially in the European Union (EU) region, none of the firm characteristic had a statistically significant influence on firms’ decision to become an exporter. This shows the general reluctance of firms about becoming exporters during the 2008 financial crisis.

As a result, we can deduce that the idiosyncratic peculiarities of crisis and the dynamics specific to certain periods interact and influence firms’ decisions to become an exporter.

Tendency to Continue Exports

Crises have different impacts on firms’ decisions to continue or cease exporting. During the 1994 crisis while profitable and quality oriented exporters were able to survive in export markets; in 2001 crisis, firms that had high intangible competitiveness and profitability and no credit constraints were able to survive. As for the 2008 financial crisis, not only quality production and credit constraints but also productivity factor came into play. While the global economic crisis of 2008 decreased Turkish manufacturing firms’ propensity to become exporters, it also lowered the likelihood of survival of small and less productive exporters in export markets. During the 2008 financial crisis, firms that were mainly exporting to the EU market had troubles in conducting business, and this shows the side effects of dependence on a single market. In this respect, focusing on policies that would help diversification of export markets may support the contribution of exports to economic stability during crises.

To sum up, even if firms’ decisions about exports are stable, it can be asserted that crises can lead to some dramatic changes in export behaviors of firms. In this context, it is very important to take into account the peculiarities of the period while determining incentives and measures to be introduced during economic fluctuations. When domestic demand is low and TL has a relative price advantage due to depreciation of the Turkish lira, policies should focus on encouraging new companies to go into export markets. At times of credit constraints, policies underpinning financing conditions should be implemented. Lastly, when external demand is low against limited contraction in domestic demand and limited depreciation in the Turkish lira, policies should focus on encouraging firms to stay in the export market.

[1] For details of the study, please see Atabek-Demirhan and Ercan (2017).

[2] One of the key reasons for the observed persistence in exporter status is the existence of sunk-costs; see Özler et al. (2009) and Atabek-Demirhan (2016).

[3] Tendency to start exporting can exceed the 20 percent average during crisis times. For instance, in the 1994 financial crisis, the ratio of first-time exporters was 32.5 percent, significantly higher than the average.

References:

Atabek-Demirhan, A. (2016). “Export behavior of the Turkish manufacturing firms.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 52(11), 2646-2668.

Atabek-Demirhan, A. and Ercan, H. (2017). “Export propensity and export volume of manufacturing firms during crises: Firm-level analysis of Turkish exporters.” Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey, Working paper (forthcoming).

Özler, Ş., Taymaz, E. and Yılmaz, K. (2009). “History matters for the export decision: Plant-level evidence from Turkish manufacturing industry.” World Development, 37(2), 479-488.