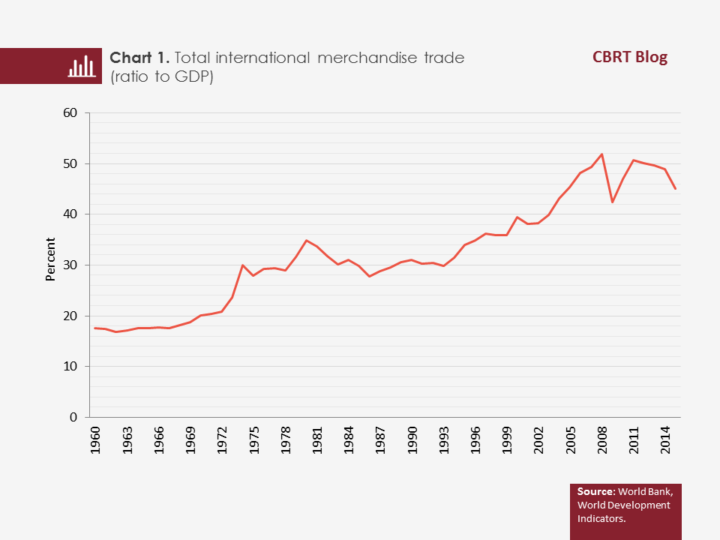

The volume of global trade, backed by the globalization trend in the course of 30 years prior to the 2008 crisis, recorded an annual growth of above 5 percent on average, but lost impetus and flattened in the post-crisis period [Domit and Shakir, 2010]. Likewise, while the ratio of total global merchandise trade to total GDP peaked prior to the global crisis, it reversed in the post-crisis period [Chart 1]. Both cyclical and structural factors had a role in this slowdown. What is meant by cyclical factors is the weakness in the global growth performance. This weakness was also accompanied by the weakening in investments, which are considered the major impulse behind the growth of world trade [Bussière et al., 2013].

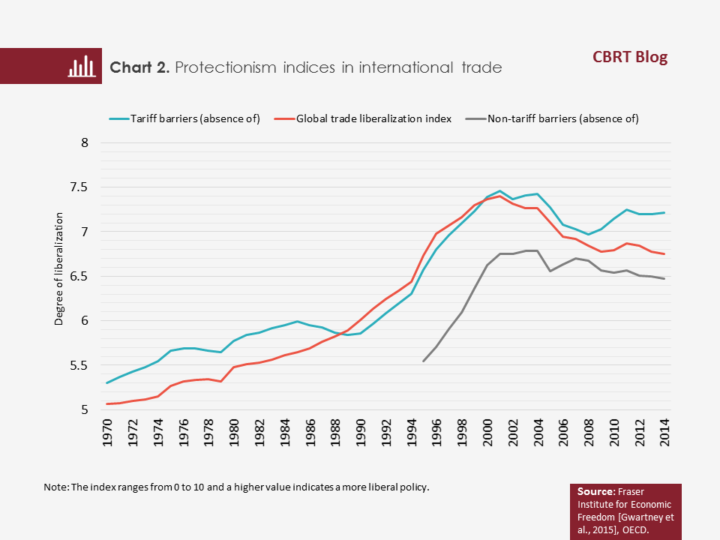

The most important structural factors are (1) stagnation in liberalization processes and (2) increased protectionist stances in world trade. Multilateral foreign trade agreements such as NAFTA and EU, which had been designed and effected in the 1980s and 1990s, accelerated the liberalization trend in international trade. During this process, “global value chains” that encourage vertical specialization, which we mean the manufacture of intermediate components used in the production of a specific product by different countries, thus forge a direct link between the production activity and the world trade volume gained major importance and strengthened the liberalization trend. In addition to the stagnation of global integration processes from the early 2000s, protectionism turned into a dominant trend all over the world after China became a far more important player in terms of high value added production with the country’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) [Chart 2]. Despite the increased protectionist stance, the involvement of China in global value chains gained impetus and sustained a strong uptrend in international trade until the 2008 crisis [Kee and Tang, 2016]. However, with the significant deceleration of intermediate goods imports on a global level in the post-crisis period, growth rates of world trade volume also fell significantly.

Following the 2008 crisis, international organisations such as the OECD and G20 sought to support the global recovery by reducing the protectionist practices in foreign trade. However, none of the efforts aiming to prevent imposition of new trade restrictions and to reduce the existing ones managed to generate the desired outcomes. Trade restrictions in G20 countries even increased and liberalization endeavors weakened. Besides, protectionism changed form and geography, and thus continued to dampen world trade [Barone and Bendini, 2015]. According to the WTO Report on trade measures of G20 countries, while a total of 145 new trade-restrictive measures were implemented in these countries between October 2015 and May 2016, the average number of such measures applied per month since 2009 recorded its highest level during this period [WTO, 2016]. The same report indicates the removal of only 387 out of 1,583 protectionist measures that had been in place in G20 countries since 2008. Therefore, contrary to the expectation of an even stronger liberalization process in the aftermath of the global crisis, it weakened, and reinforced the slowdown in world trade volume. Considerations regarding unfair competition caused by China’s foreign trade policies and anti-dumping measures adopted by advanced economies against Chinese products were influential in the increase of the protectionist stance.

The likelihood of a reversal in liberalization and integration processes driven by the EU and the US in the period ahead has started to be openly discussed on international platforms. In addition to the changing international political composition, the global liquidity glut that emerged after the 2008 crisis and the financial deterioration it caused on a global basis, primarily in emerging economies due to its rapid mobility, bring about strategic moves called “currency wars”, which index countries’ monetary and exchange rate policies to other countries’ steps rather than their own priorities. Despite the emphasis placed on measures restoring global coordination of economic policies in the G20 or on similar platforms, countries’ inclinations to take individual steps by prioritizing their own problems have strengthened. As a natural consequence of these developments, the protectionism increases, the weight of global value chains in production decreases and, in addition to the stagnation in world trade, the slowdown in global growth as well as in investments becomes more pronounced.

In addition to the deceleration in external demand, the increasing protectionist tendencies in world trade are repressing the international trade performance of our country, too. However, along with the skills of Turkish exporters in finding new markets, the steady increase in our exports to the EU keeps our exports performance relatively lively. Despite increasing protectionist tendencies all over the world, the steps currently being taken and those being discussed in Turkey with regard to openness to external markets, competitiveness, efficiency, innovativeness and liberalization are noteworthy. Once the stability improves in the surrounding geography, Turkey’s foreign trade performance is expected to diverge positively by displaying a strong trend.

Bibliography:

Barone, B. and R. Bendini (2015). “Protectionism in the G-20”, Directorate-General for External Policies, European Parliament.

Bussière, M., G. Callegari, F. Ghironi, G. Sestieri and N. Yamano (2013). “Estimating Trade Elasticities: Demand Composition and the Trade Collapse of 2008-2009”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 5, 118-151.

Domit, S. and T. Shakir (2010). “Interpreting the World Trade Collapse”, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 50, 183-189.

Gwartney, J., R. Lawson and J. Hall (2015). "Economic Freedom of the World, Annual Report 2015", Fraser Institute.

Kee, H. L. and H. Tang (2016). “Domestic Value Added in Exports: Theory and Firm Evidence from China”, American Economic Review, 106, 1402-1436.

WTO (2016). “Report on G20 Trade Measures”, WTO OMC.