The success of disinflation efforts is strongly tied to improvements in both household inflation expectations and service sector inflation. Recently, the recovery in household inflation expectations has lagged behind that of market participants. At the same time, the rigidity of service prices has emerged as a factor slowing the decline in overall inflation (see Charts 1 and 2). This blog post examines the supply-side relationship between household inflation expectations and realized service sector inflation.

Existing work indicates a possible pass-through effect from actual inflation to household inflation expectations.[1] In particular, price increases in critical products such as food and fuel can further elevate household inflation expectations.[2] Conversely, heightened inflation expectations also influence realized inflation. When households expect higher inflation, their propensity to consume tends to increase, which puts upward pressure on goods and services prices through demand-side dynamics.[3]

Moreover, this two-way relationship between expected and realized inflation reflects both supply-side and demand-side factors, as households are also providers of certain services. For example, households directly determine the prices of services such as domestic work, hairdressing, and photography, which are included in the CPI basket. Therefore, the link between household inflation expectations and service inflation may also be driven by supply-side dynamics.

To analyze supply-side effects, we classify items such as household services and hairdressing as services provided by households.[4] Based on this classification, inflation in services provided by households appears to have been higher than both the CPI index and the CPI-services index in recent years (Chart 3).[5] Between January 2020 and November 2024, the price index of services provided by households increased by 21% more than the overall CPI and by 11% more than the CPI-services index.

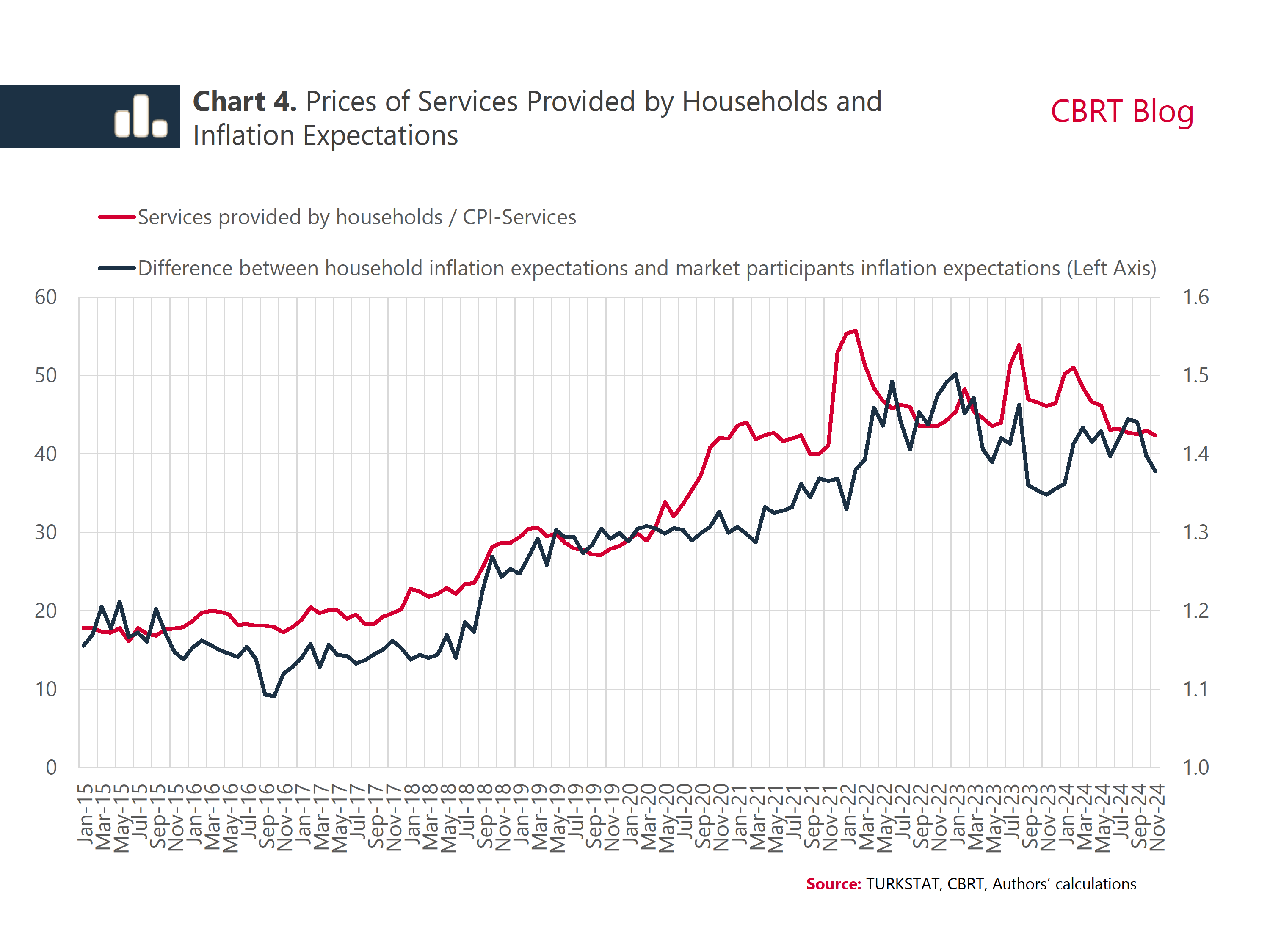

A more detailed analysis reveals that this divergence in price increases is closely related to the inflation expectations of households. In fact, in periods when the difference in the household sector’s inflation expectations is skewed to the upside, the relative prices of household-provided services also increase against other items in services (Chart 4). This implies that households adjust the prices of the services they provide based on their deteriorating inflation expectations.

When we test the existence of this relationship econometrically, we obtain results that confirm our preliminary findings. Our results suggest that the inflation of services provided by households is positively correlated with household inflation expectations (Chart 5). According to the regression results, after a 10% increase in the difference between inflation expectations of households and the market, services provided by households in the following month saw a monthly inflation increase of 0.42 points, that is 42 basis points, compared to all other products (CPI).[6] Besides, results suggest that this relation is not only specific to the periods of wage increases.[7] Excluding periods of wage increases, a 10% deterioration in inflation expectations implies a monthly inflation increase of 24 basis points in the following month for these services compared to all other products. This relationship points to a monthly inflation of 19 basis points when only service items are used as comparison group.

To sum up, the findings suggest that high household inflation expectations is one of the determinants of the price rigidity in services through the channel of services provided by households. Therefore, our results show that the recent improvement in household inflation expectations will support the disinflation process not only through the demand side but also through the supply side.

[1] Although there are periodic differences, studies suggest that there may be a high correlation between actual inflation and expected inflation. (Binder and Kamdar, 2022).

[2] Previous studies suggest that food inflation, Brent oil and the dollar exchange rate are more influential on consumers' forecast revisions (CBRT, 2024).

[3] Studies suggest that inflation expectations affect consumption and savings decisions within the set of subjective expectations through the consumption Euler equation (D’Acunto et al, 2022).

[4] The following CPI basket items are considered as services provided by households: 03140-Cleaning and repair of clothing, 03220-Maintenance and repair of footwear, 05330-Repair of household appliances, 05621-Household services (domestic worker wages), 07230-Maintenance and repair of personal transportation vehicles, 09150-Maintenance and repair of audio-visual equipment, 09421-Photography services, 12111-Hairdressing services for men, 12112-Hairdressing services for women, 12400-Child care services (nurseries). The rent item in the CPI is not included in the analysis as despite being provided directly by households, it can be deemed as a return on capital rather than a service.

[5] A similar trend also prevails in the index constructed by including sectors such as rents, as well as meals and beverages served in restaurants, patisseries, cafes, etc.

[6] In the regression analyses, for the “difference between household and market inflation expectations”, different lag lengths were included in the model instead of time fixed effects, and the interpretation of the findings did not change.

[7] Since price hikes in labor-intensive sectors may be more pronounced during periods of wage increases, we also conducted regression analyses excluding periods of wage increases. Considering that there may be carryovers in wage hikes, we determined January-February and July-August as wage increase periods.

References

Binder, Carola, and Rupal Kamdar. 2022. “Expected and Realized Inflation in Historical Perspective.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 36 (3): 131-56.

D'Acunto, F., Malmendier, U., & Weber, M. (2023). What do the data tell us about inflation expectations? In Handbook of economic expectations (pp. 133-161).

CBRT, Inflation Report 2024-III, Box 3.1 Determinants of Sectoral Inflation Expectations