According to a widely-believed anecdote, the French Emperor Napoleon warned about China nearly 300 years ago, saying “Let her sleep, for when she wakes she will shake the world”. Having lain dormant for several centuries at that time, the Chinese economy awoke from its long sleep in the last quarter of the 20th century and resumed interactions with the outside world, and hence the prophecy was fulfilled. Today, any understanding of a global matter that does not include China will be insufficient, though not entirely false. In fact, some of the economic issues that the world has grappled with over the past one year involve, first and foremost, China’s economic slowdown and measures taken by its government. From 1979 to 2009, the Chinese economy grew by more than 10% on average, and has since been gradually decelerating. According to the latest forecasts of the IMF, China’s economic growth will sink to a 30-year low, growing by only 6.1% and 5.8% in 2019 and 2020, respectively. Additionally, the US-China trade spat has been dominating global economic news in recent months. In this period, many public, private or academic studies dealt with spillovers from China’s slowdown to the rest of the world, emerging economies in particular.

We took a different approach to show the growing significance of the Chinese economy across the globe and evaluated how frequently China comes up in the IMF’s semiannual World Economic Outlook (WEO). As seen in Chart 1, China has received an ever-increasing weight in the WEO over the past 20 years, except during the global financial crisis. In fact, on average, WEO texts and charts mentioned China more often than the US and the euro area/Europe between 2014 and 2018 [1].

Having joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, China integrated rapidly into the world economy and grew to become a key player to have direct implications for many economies through trade and finance. This natural influence of the world’s greatest exporter and second largest importer comes up in changing ways over time. For a decade after its accession to the WTO, China remained on the global economic agenda with issues such as the impact of cheap Chinese exports on global inflation dynamics or the impact of surging Chinese foreign exchange reserves on US bond yields due to the savings surplus. Following the global financial crisis, China emerged on the trade front as the global leader to determine the demand for raw materials, and on the financial front, many began to discuss if risks such as rapidly rising debt ratios, shadow banking and the housing market bubble posed a systemic risk to the Chinese and world economy.

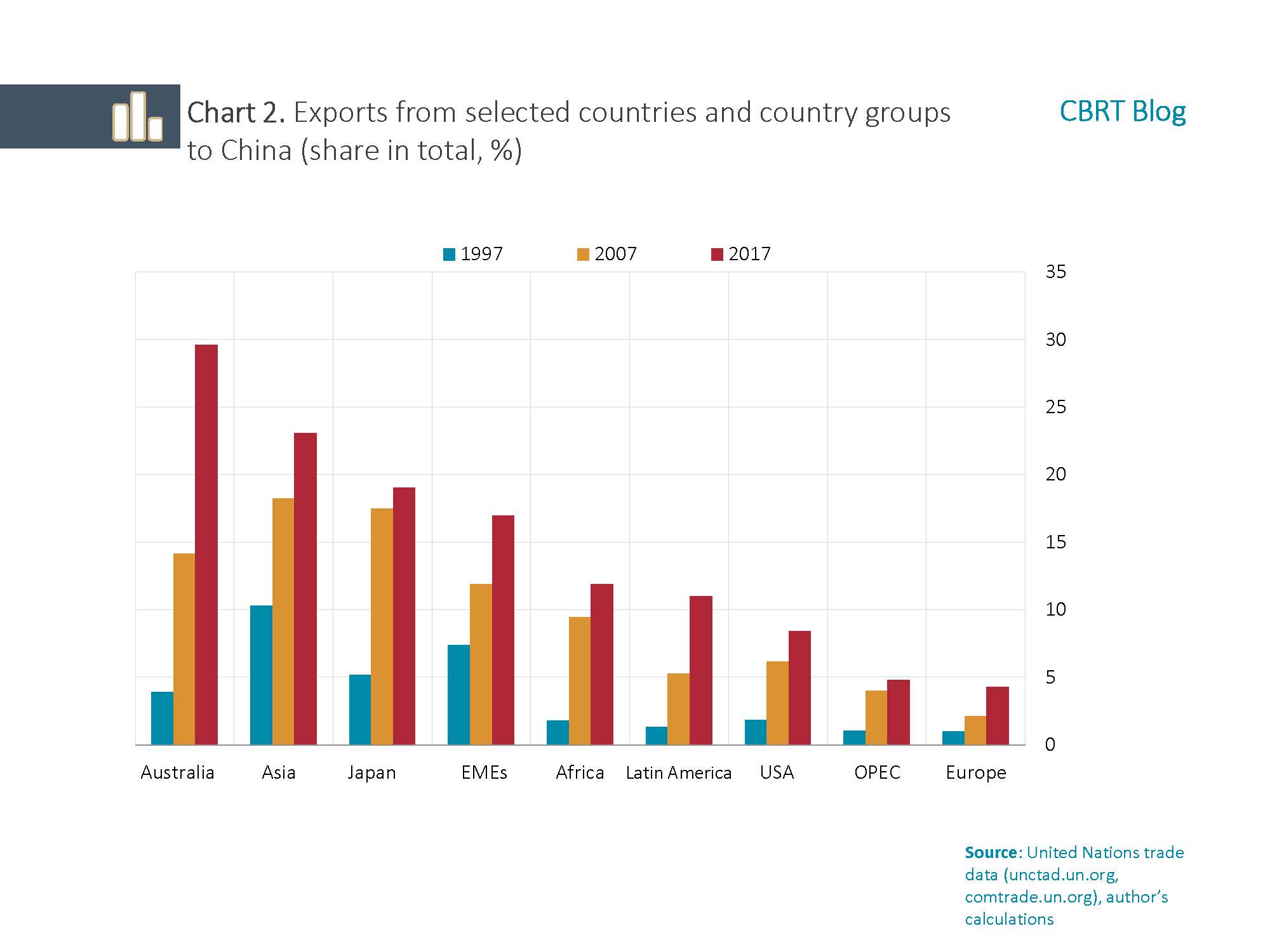

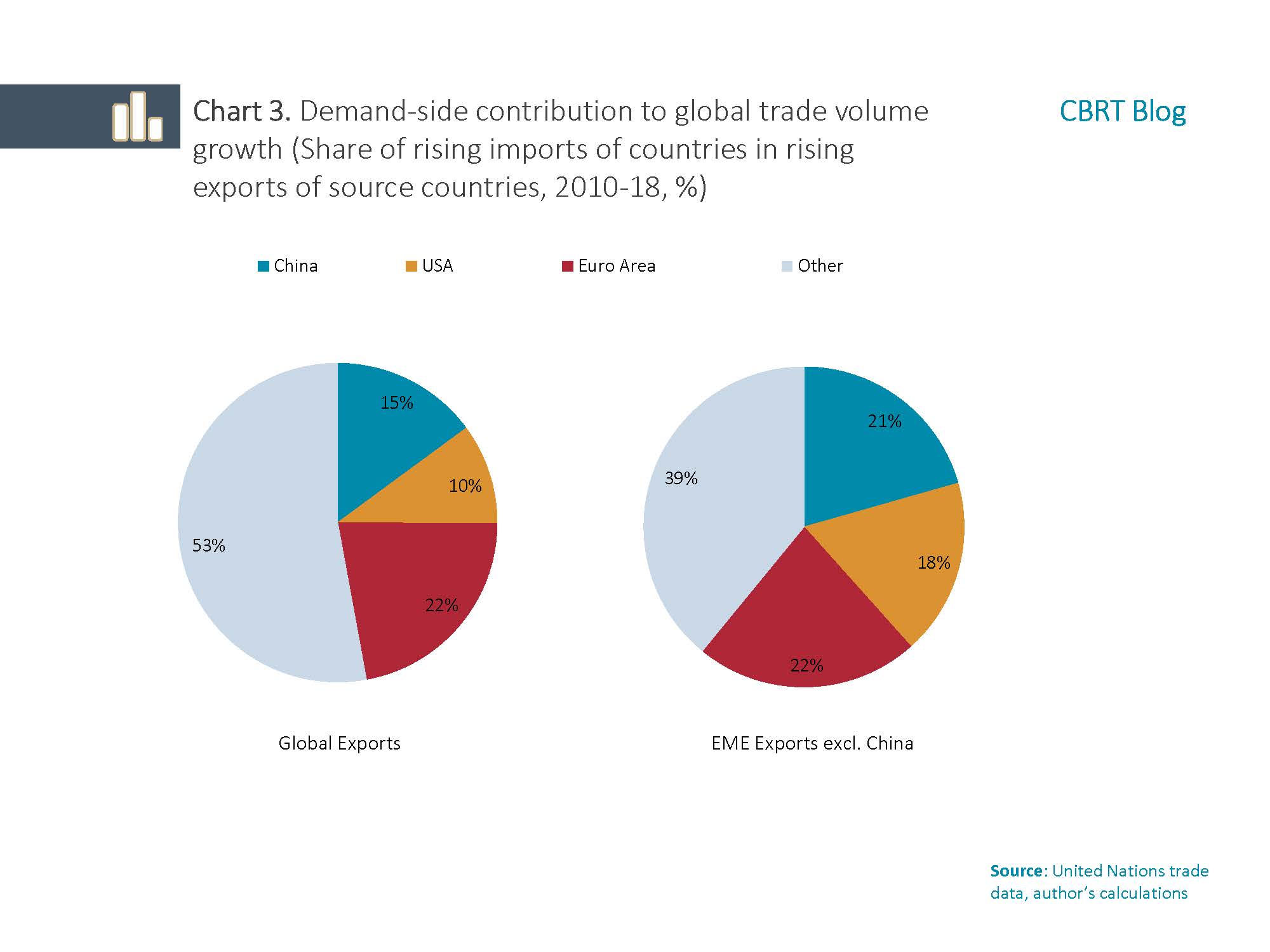

Among the above interactions, the trade channel is more prominent and easily detectable. Almost every major economy has seen its exports to China increase in the past 20 years (Chart 2). As a result, China has become the largest contributor on the demand side to the world trade volume that grew threefold between 2000 and 2018 (Chart 3).

Countries that are more exposed to changes in the Chinese economy through trade are mostly from Asia Pacific due to both their geographical proximity and their position in the value-added chain. These countries are followed by exporters of raw materials, particularly from Africa and Latin America. Due to the abovementioned factors, countries vulnerable to changes in China include Japan and Australia, though they are among advanced economies, which demonstrates that emerging economies are not necessarily the only ones exposed. These trade implications of China are also documented by academic studies.

Understanding how China affects the global economy through finance calls for a more detailed analysis. An IMF report published in 2016 gives a comprehensive account of such financial implications. The report asserts that the lack of a fully-liberalized capital account helps China have less financial implications for the rest of the world. According to the report, China’s foreign assets and liabilities accrued up to USD 11 trillion in 2015, equaling the likes of Japan and France, both advanced economies, and a considerable portion of this amount is made up of foreign exchange reserves and foreign direct investments. China’s foreign assets and liabilities reached a total of USD 12.5 trillion as of the end of 2018 while its net international investment position posted a surplus of USD 2.1 trillion (about 15.9% of the GDP). Meanwhile, data from China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange, SAFE, show that the net foreign position of Chinese banks hovered around a relatively low USD 181 billion (around 1.3% of the GDP) at the end of 2018, suggesting that a possible financial collapse in China will have little spillover effect on the world. In fact, in its above report, the IMF estimated that the Capital Adequacy Ratios (Tier 1) of banks holding positions in China will not fall below the 6% Basel III minimum even in the worst-case scenario.

According to the IMF Report, developments in China spill over across global markets through secondary channels such as global risk appetite or the effects of expectations over the Chinese economy on prices of raw materials, rather than the Chinese asset market. The study also states that bad news about the Chinese economy has a more profound impact on global asset prices than the trading in Chinese markets, and such news triggers a flight from countries that are vulnerable and/or exporting raw materials to “safe haven” assets.

How Exposed is Turkey to China’s Economy?

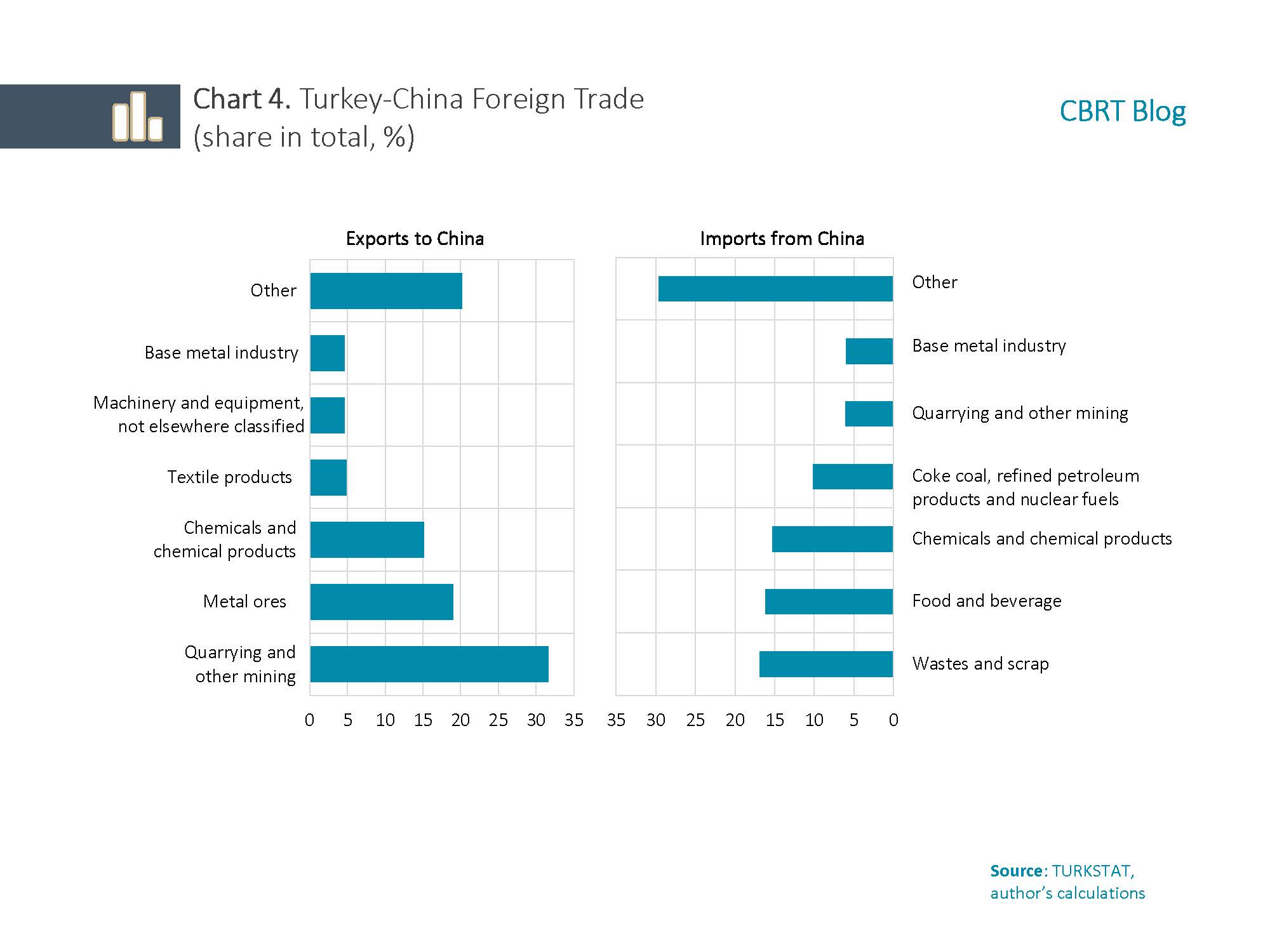

According to TURKSTAT data, Turkey recorded exports worth USD 2.9 billion to China in 2018. Holding a share just below 2% in Turkey’s total exports, China does not seem to pose a big risk to our exports [2]. However, among sectors that have economic ties with China, mining appears particularly vulnerable to the economic developments in China. The mining industry [3] accounted for about USD 1.5 billion worth of exports to China in the last year, representing half of total Turkish exports to China and 45% of total mining exports (Chart 4). Therefore, business cycles in China can affect the mining industry through both trade and prices of raw materials. On the other hand, as our exports to oil and natural gas exporters such as Middle Eastern and Central Asian economies and Russia account for nearly 25% of total Turkish exports, Turkey might face second-round effects from economic developments in China.

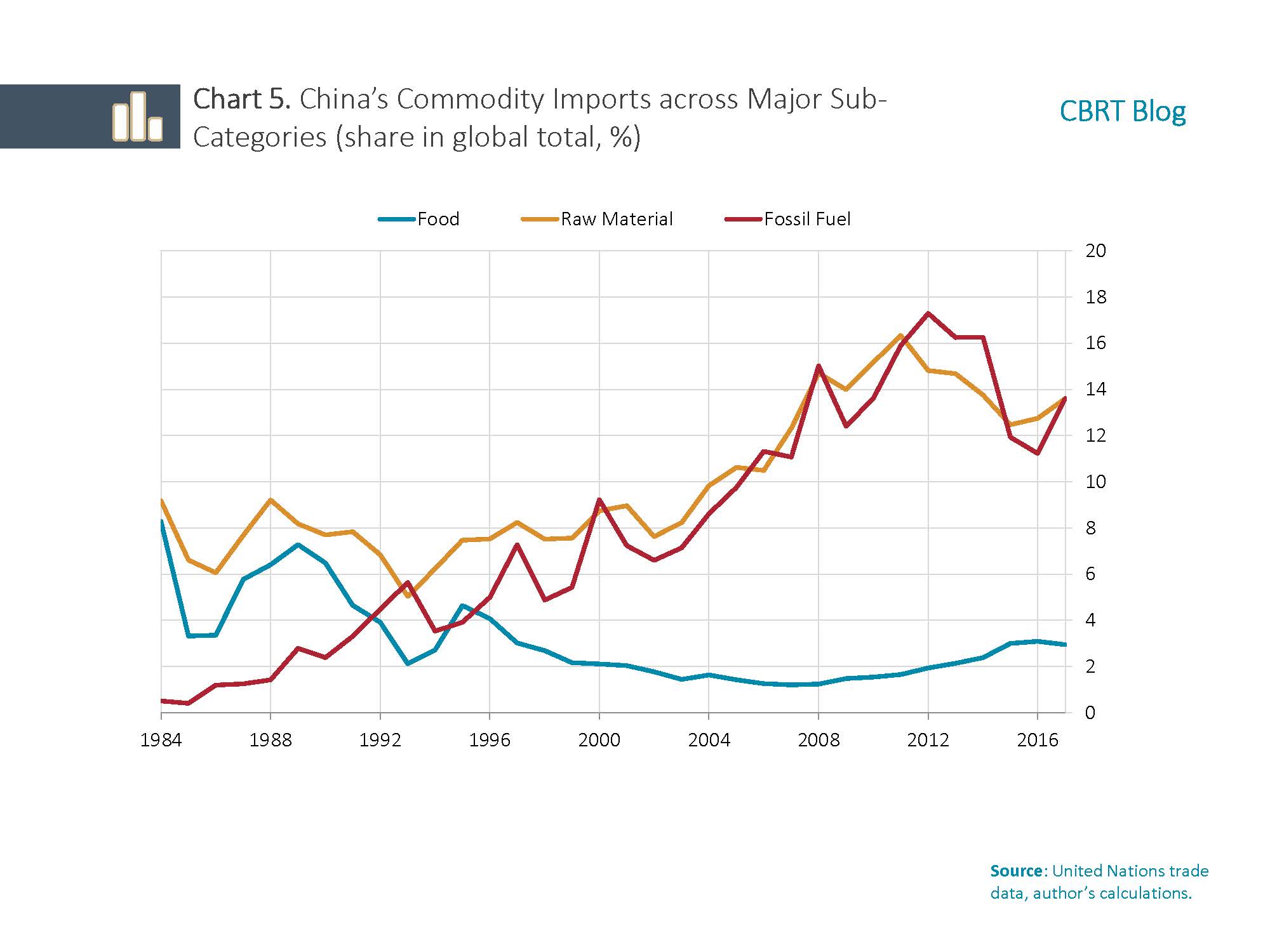

Currently, the most obvious channel through which the turmoil in China can affect the overall Turkish economy, both positively and negatively, is the prices of raw materials. China has been the biggest oil importer in the world since 2018, and its energy demand is increasing every day. Thus, being an importer of raw materials, particularly energy, Turkey may see less pressure on its current account deficit and inflation from a possible Chinese economic slowdown. On the other hand, food imports that resumed their uptrend in the last decade due to China’s consumption-oriented economic transformation may push global food prices higher and higher, which can be noted as an upside risk (Chart 5).

In conclusion, although Turkey currently seems to be less exposed to China (except for industries such as mining), with China’s ever-increasing weight in the global economy, it would be reasonable to expect direct and indirect effects to become more pronounced. Moreover, the effect that China will have on global financial markets should be monitored carefully in terms of any foreign exchange and asset market turbulence it may cause through changes in global risk appetite.

[1] This analysis does not include the tables in the IMF’s WEO reports.

[2] Turkey’s USD 20.7 billion worth of imports from China in 2018 generated a foreign trade deficit of USD 17.8 billion against this country.

[3] “Mining and Quarrying” as classified by the two-digit level of ISIC Rev 3.

Reference

Spillover Notes No: 5, Spillovers from China: Financial Channels, IMF Spillover Task Force, September 2019.

World Economic Outlook, IMF, 1999-2019.